Most of my life has revolved around animals. That covers my years with wild animals as a wildlife biologist but also includes work at several domestic animal shelters. This is a story about a queen who lived at one such shelter.

Beatrice was a lovable, chubby, snuggly pit bull with a perennial smile and a slowly, constantly wagging tail. Bea was found chained to a highway guardrail. Motivated by a latent stirring of humanity, the person who abandoned Beatrice on the side of the road left a bowl of water and some dog food to assuage their guilt.

The county’s Humane Officer suspected that she was a farm dog who, at seven years old, had outlived her usefulness as a profitable breeder. As likely as that explanation was, the reasons for her rejection ultimately didn’t matter; Bea was welcomed into our animal shelter, along with dozens of other animals struggling to find homes.

Of the millions of animals – cats, dogs, horses, reptiles, birds and small mammals like gerbils and Guinea pigs – in shelters across the country, some are considered more ‘adoptable’ than others. Factors that affect adoptions vary by region, season, species, breed, and in other less quantifiable ways. The reality is that, in the world of pet adoptions, the odds favor certain animals.

The odds were not with Beatrice. The first strike against her was genealogy. ‘Pit bull’ is not a breed recognized by the AKC or the FCI. The term usually refers to several mid- to large-size Staffordshire terrier breeds whose increasing popularity over the last 30 years has catapulted them into the majority of many shelter populations. A national surplus of these dogs means that they are easy to find; they are not in demand for adoptions.

Bea’s second strike was her age. At seven years old, she didn’t appeal to people searching for puppies.

The shelter’s board of directors and the kennel staff recognized these facts immediately. They are inescapably familiar realities to those trying to find forever homes for abused, abandoned or simply unwanted dogs.

The third strike against Bea was . . . substantially harder to bear. Soon after she arrived at the shelter, Beatrice developed a large tumor on her neck. One of our consulting veterinarians removed the tumor. Within months, another sizeable tumor took its place. After a second operation, the vet lamented that Beatrice did not have enough skin remaining to close another large suture if future tumors appeared.

Her neck healed but staff noticed other masses as the months passed. The prognosis was unavoidable: Beatrice was going to die. The virulent cancer in her body could not be stopped.

We knew that the best thing we could do for Bea was find her a home where she could live out her remaining days in peace and contentment. The board of directors, the kennel staff and the shelter volunteers made it their mission to find a place for Bea. They relentlessly contacted people and organizations across the country.

By the time of this definitive diagnosis, Beatrice had spent almost a year at the shelter. She was an 8 year-old member of an overly-common and misunderstood breed of canine with a chip on her shoulder (she didn’t get along with other dogs). And she was dying. I did not hold out much hope.

Bea, though she grew weak at times, never wavered in her sweet, affectionate disposition. She continually greeted us with a wiggling rear end and her squinty, genuine smile whenever we entered her room.

Then, after months of appeals to non-profits and rescues and the public, a woman appeared. She consulted with the shelter’s staff, learning about Bea’s medication needs, how to care for her, and her long-term prognosis. Despite it all – even the recognition that an emotional investment in Beatrice could be painfully short – the woman took Beatrice home.

This simple act of unexpected kindness restored my faith in the better, if grudging, impulses of humanity but Bea was not quite done with me.

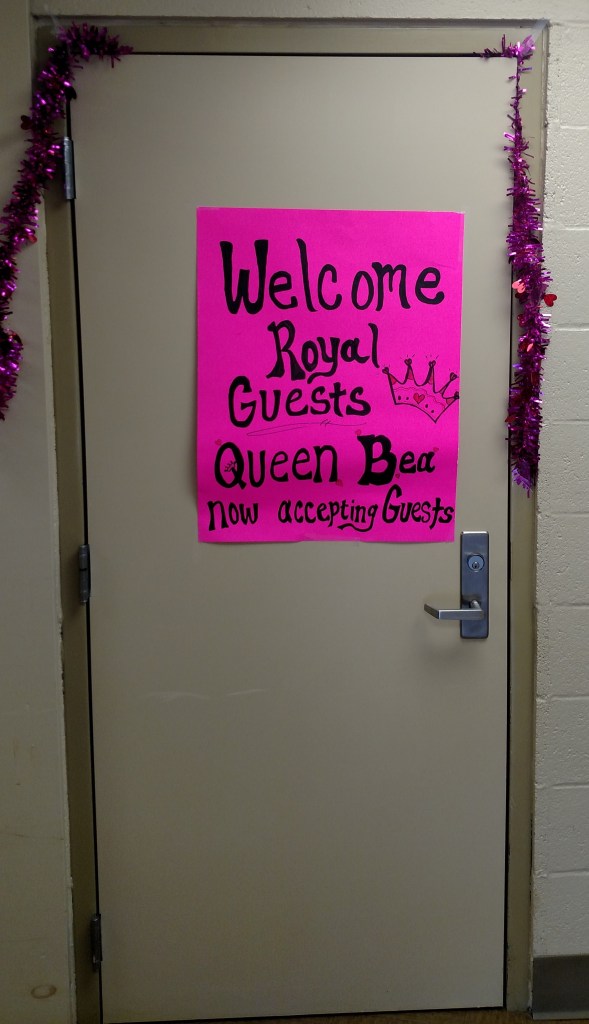

The shelter held a celebration, billing it as a chance to say goodbye to Queen Bea. People donated hot food, baked goods, dog treats, and other items to raise money for Beatrice’s new life.

The community raised hundreds of dollars, showing up in droves as adults dragged children to see Queen Bea and vice versa. People who had never been the shelter before stood next to those who spend much of their free time there. Adults took pictures as their children hugged Beatrice and eventually bestowed a tutu and a tiara on the dog.

One little girl arrived wearing her best blue princess gown to meet the Queen. Her mother explained that she frequently brought the girl to the shelter to look at the cats but the little one was afraid of dogs. Upon hearing about Beatrice, the girl wanted to meet her and, from what I could tell, the Princess did not fear the Queen that day.

A few of us were aware that Beatrice was not feeling particularly well on the day of the party. She had little appetite and was weak. It is fair to say, however, that this was not apparent to most of her visitors.

My background and training in animal behavior has cautioned me against anthropomorphizing, or ascribing human motivations to animals. Yet I have never before witnessed a dog so clearly calculating, so patiently engaged, and so completely selfless. I firmly believe that Beatrice consciously, and with a sense of altruistic purpose beyond anything I expected, put on a show that day because she sensed what those people needed from her.

All of those people, young and old, needed to know that Beatrice was happy. They needed, on some deep and perhaps inescapably human level, to know that things were going to work out for her. I doubt many of her visitors could have explained this need but they demonstrated it when they bought armloads of uneaten baked goods and dropped money into an already-full donation box.

So happiness was what Beatrice showed her visitors that day. Queen Bea didn’t reveal her suffering or demonstrate her discomfort. Instead, she wagged her tail and wiggled and smiled for her fans. All afternoon she licked kids’ painted faces and charmed adults who might have run from the sight of a pit bull any other day. When the party ended, Bea was very tired. She returned to her new home for some well-deserved rest.

I never saw Beatrice again. The Queen died a less than a week after that summer day spent with a crowd of well-wishers and one little princess.

I’ve had time to reflect on Bea’s passing. Mostly, I suppose, I feel relieved. We got Beatrice the pit bull into a home – a real home, peaceful and quiet and happy – before she died. It was in the nick of time but we did it.

I suppose that may be confusing to some. After all, Bea did not live out a long and easy life in her new home. That fairy tale wasn’t possible for this dog but she still got her happy ending. Despite all her troubles, Beatrice enjoyed a few blissful, halcyon days in a safe, comfortable place with constant companionship and adoration. That was a victory in a business where such triumphs can often feel few and far between.

In the end, when Queen Bea lay down her head and surrendered her soul like a child releasing a balloon, she knew that she was surrounded by love. True to her nature, she never complained or cried about how unfair life had been to her. I cannot say the same for myself.

I will always remember Bea’s habit of presenting the best of herself to the people around her. Even during some of the most painful times of her life, Beatrice delighted those near her. Maybe we would all do well to learn from that example.

A very nice story, Troy. Thanks!

LikeLike